Some Words about True and False Jihad

“Let not your hatred of other men turn you away from justice. Be just…that is closer to piety.” Koran 5:7

“Be swift to hear, slow to speak, slow to wrath, for the wrath of man does not produce the righteousness of God…” James 1:19

The word jihad has been much abused by a tiny, but spectacularly successful minority of angry Muslims. Their success has been to pervert a good and holy word into a bad word, one that is associated in the non-Muslim world with Muslims killing people in God’s name. Jihad and violence are now widely viewed in the public mind as synonymous with Islam. Such thinking fuels western Islamophobia which, in turn, encourages various forms of aggression—verbal and otherwise—that lends credence to the jihadist argument that the West hates Islam and wants to destroy it. And that is their most potent recruiting tool.

This sense of threat to Muslims’ religious identity can best be understood among secular people if we think of Islam representing what flag and home represent to us. Defending and dying for one’s flag is considered patriotism, and for many Muslims, Islam is flag and home. For those Muslims who have not yet been secularized—faith is a primary source of identity, much as it is for a Trappist monk or Mennonite. But when they fight, especially in a violent manner, Westerners call it fanaticism.

As the following lengthy article by a London based Muslim scholar argues—from both texts and from history—the jihadist are making up their own law and like all politically motivated leaders, want to wrap their cause in righteousness. They do it by cherry picking scripture and inventing or dismissing hadiths (sayings of the Prophet). God doesn’t outlaw fighting, but does give guidance on how to fight and why to fight. In this respect, emir Abdelkader is a model, as was Saladin many centuries before. Both are used by the author to illustrate the spirit of True Jihad.

Because of its length (22 pages), I have abridged this excellent, educational article published in 2005 in the Journal of Zaytuna by Reza-Shah Kazemi. (To read the full version in PDF format, click here: From the Spirituality of Jihad to the Ideology of Jihadism.)

From the Spirituality of Jihad to the Ideology of Jihadism

Reza Shah-Kazemi

Dr. Reza Shah-Kazemi is a Research Associate at the Institute of Ismaili Studies in London. He is founding editor of Islamic World Report, and has written and edited several books and articles on such topics as the Qur’an and Interfaith Dialogue, Comparative Religion, Jihad in Islam, Sufism, and Shi’ism.

Not an Eye for an Eye: The Emir Abdelkader

Emir with medals received from around the world following his rescue of Christians

The life-blood of terrorism is hatred; and this hatred is often in turn the disfigured expression of grievance, grievance that may be legitimate. In the present day, few doubt that the on-going injustices in Palestine and other parts of the Muslim world give rise to legitimate grievances; but there is nothing in Islam that justifies the killing or injuring of civilians, nor of perpetrating any excess as a result of hatred, even if that hatred is based on legitimate grievances. The pursuit of justice must be conducted in accordance with justice; the means should not undermine the end: “O ye who believe, be upright for God, witnesses in justice; and let not hatred of a people cause you to be unjust. Be just, that is closer to piety.”

It would be profitable to dwell at some length at one of the most important figures of recent history, the Emir Abdelkader, leader of the Algerian Muslims in their heroic resistance to French colonial aggression between 1830 and 1847. For his conduct is a perfect exemplification of the principle enshrined in this verse, and, in general, he stands forth as a powerful antidote to many of the most insidious poisons afflicting the body politic of the Muslim world in our times. For his response to a truly despicable enemy‚ if ever there were one‚ was never tainted with the hint of injustice; on the contrary, his impeccable conduct in the face of treachery, deceit, and unspeakable cruelty put his civilized adversaries to shame. His enemy, the French, who initiated imperialistic aggression against the Muslims of Algeria, were guilty of the most horrific crimes in their ‚mission civilisatrice,‚ crimes that were in fact acknowledged as such by the architects of this mission, but justified by them on account of the absolute necessity of imparting civilization to the Arabs. This was an end which justified any means, even, ironically, the most savage.

Bopichon, author of two books on Algeria in the 1840s, states the underlying ethos of the French colonial enterprise as follows: Little does it matter that France in her political conduct goes beyond the limits of common morality at times; the essential thing is that she establish a lasting colony, and that as a consequence, she will bring European civilization to these barbarous countries; when a project which is to the advantage of all humanity is to be carried out, the shortest path is the best. Now, it is certain that the shortest path is terror. Terrorism well describes the policy carried out by the French. Testimonies abound as to the atrocities perpetrated by French forces. An evidently remorseful, if not traumatized, Count de ©risson recounts in his book La chasse a l’homme (Hunting the man) that “We would bring back a barrel full of ears harvested, pair by pair, from prisoners, friends or foes,” inflicting on them “unbelievable cruelties.” The ears of Arabs were worth ten francs a pair and their women remained a perfect prey. Official French reports eventually registered with shame these monstrous acts. A Government Inquiry Commission report of 1883 frankly admitted: “We massacred people carrying [French] passes, on a suspicion we slit the throats of entire populations who were later on proven to be innocent; we tried men famous for their holiness in the land, venerated men, because they had enough courage to come and meet our rage in order to intercede on behalf of their unfortunate fellow countrymen.”

How did the Emir respond to such unbridled savagery? Not with bitter vengefulness and enraged fury but with dispassionate propriety and principled warfare. At a time when the French were mutilating Arab prisoners, wiping out whole tribes, burning men, women, and children alive; and when severed Arab heads were regarded as trophies of war‚ the Emir manifested his magnanimity, his unflinching adherence to Islamic principle, and his refusal to stoop to the level of his “civilized” adversaries by issuing the following edict: Every Arab who captures alive a French soldier will receive as reward eight douros. “Every Arab who has in his possession a Frenchman is bound to treat him well and to conduct him to either the Khalifa [Caliph] or the Emir himself, as soon as possible. In cases where the prisoner complains of ill treatment, the Arab will have no right to any reward.“ When asked what the reward was for a severed French head, the Emir replied, twenty-five blows of the baton on the soles of the feet.

The Emir's prayer rug

One understands why General should place alongside Jugurtha‚ but also as a kind of prophet, the hope of all fervent Muslims. When he was finally defeated and brought to France, before being exiled to Damascus, the Emir received hundreds of French admirers who had heard of his bravery and his nobility; the visitors by whom he was most deeply touched, though, were French officers who came to thank him for the treatment they received at his hands when they were his prisoners in Algeria. One should note carefully the extraordinary care shown by the Emir for his French prisoners. Not only did he ensure that they were protected against violent reprisals on the part of outraged tribesmen seeking to avenge loved ones who had been brutally killed by the French, he also manifested concern for their spiritual well-being: a Christian priest was invited by him to minister to the religious needs of his prisoners. In a letter to Dupuch, Bishop of Algeria, with whom he had entered into negotiations regarding prisoners generally, he wrote, Send a priest to my camp, he will lack nothing.

Likewise, as regards female prisoners, he exercised the most sensitive treatment, having them placed under the protective care of his mother, lodging them in a tent permanently guarded against any would-be molesters. It is hardly surprising that some of these prisoners of war embraced Islam, while others, once they were freed, sought to remain with the Emir and serve under him. The Emir’s humane treatment of French prisoners was kept secret from the French forces; had it leaked out, the result would have been devastating for the morale of the French forces, who had been told that they were fighting a war for the sake of civilization, and that their adversaries were barbarians. As Colonel Gery confided in the Bishop of Algeria, “We are obliged to try as hard as we can to hide these things [the treatment accorded French prisoners by the Emir] from our soldiers. For if they so much as suspected such things, they would not hasten with such fury against Abdelkader.”

Over one hundred years before the signing of the Geneva Conventions, the Emir demonstrated the meaning not only of the rights of prisoners of war but also of the innate and inalienable dignity of the human being, whatever his or her religion. Also highly relevant to our theme is the Emir’s famous defense of the Christians in Damascus in 1860...The Emir then sent two hundred of his men to various parts of the Christian quarters to find as many Christians as they could. He also offered fifty piastres to anyone who brought to him a Christian alive. His mission continued thus for five days and nights, during which he neither slept nor rested. As the numbers swelled to several thousand, the Emir escorted them all to the citadel of the city...

It is estimated that in the end, no less than fifteen thousand Christians were saved by the Emir in this action; and it is important to note that in this number were included all the ambassadors and consuls of the European powers together with their families. As Charles Henry Churchill, his biographer, prosaically puts it, just a few years after the event, All the representatives of the Christian powers then residing in Damascus, without one single exception, had owed their lives to him. Strange and unparalleled destiny! An Arab had thrown his guardian aegis over the outraged majesty of Europe. A descendant of the Prophet had sheltered and protected the Spouse of Christ. The Emir received the highest possible medals and honors from all the leading western powers. The French Consul himself, representative of the state that was still very much in the process of colonizing the Emir’s homeland, owed his life to the Emir; for this true warrior of Islam. There was no bitterness, resentment, or revenge, only the duty to protect the innocent, and all the People of the Book who lived peacefully within the lands of Islam.

Gift of pistols from President Lincoln

When the Bishop of Algiers, Louis Pavy, commended the Emir’s actions, the latter replied, “The good that we did to the Christians was what we were obliged to do, out of fidelity to Islamic law and out of respect for the rights of humanity. For all creatures are the family of God, and those most beloved of God are those who are most beneficial to his family.” Then follows this passage which is clearly rooted in the universality of the Qur’anic message and the “ontological imperative” of mercy that is its ineluctable concomitant. The practical import of this universality and this mercy is expressed dramatically by the courage of the Emir in his unwavering fidelity to these principles; these are not mere words but ultimate spiritual values, for which one must be prepared to make the ultimate sacrifice if necessary: “All the religions brought by the prophets, from Adam to Muhammad, rest upon two principles: the exaltation of God Most High, and compassion for His creatures. Apart from these two principles, there are but ramifications, the divergences of which are without importance. And the law of Muhammad is, among all doctrines, that which shows itself most attached to, and most respectful of, compassion and mercy. But those who belong to the religion of Muhammad have caused it to deviate. That is why God has caused them to lose their way. The recompense has been of the same nature as the fault.”

What we are given here is a concise and irrefutable diagnosis of the contemporary malaise within the Islamic world: since the compassion that is so central to this great religion has been subordinated to anger and bitterness, the mercy of God has been withdrawn from those who have caused it to deviate. This is in accordance with the well-known saying of the Prophet: “He who shows no mercy will not have mercy shown him‚” as well as with this verse of the Qur’an: “In their hearts is a disease, so God increased their disease.” This disease of hard-heartedness needs to be accurately diagnosed; and, if we are to take seriously the greatest warriors of our recent past, a key ingredient of the remedy is universal compassion.

It is interesting to note that another great warrior of Islam, Imam Shamil of Dagestan, hero of the wars against Russian imperialism, wrote a letter to the Emir when he heard of his defense of the Christians. He praised the Emir for his noble act, thanking God that there were still Muslims who behaved according to the spiritual ideals of Islam: ‘Know that when my ear was struck with that which is detestable to hear, and odious to human nature‚ I allude to the recent events in Damascus concerning the Muslims and the Christians, in which the former pursued a path unworthy of the followers of Islam ... a veil was cast over my soul ... I cried to myself: Corruption has appeared on the earth and at sea, because of what men’s hands have wrought [Qur’an 30:41]. I was astonished at the blindness of the functionaries who have plunged into such excesses, forgetful of the words of the Prophet, peace be upon him, “Whoever shall be unjust towards a tributary, whoever shall do him wrong, whoever shall deprive him of anything without his own consent, it is I who will be the accuser on the day of judgement”...Oh, what sublime words! But when I was informed that you have sheltered the tributaries beneath the wings of goodness and compassion; that you had opposed the men who militated against the will of God Most High, I praised you as God Most High will praise you on the day when neither their wealth nor their children avail [Qur’an 3:10]. In reality, you have put into practice the words of the great apostle of God Most High, bearing witness to compassion for His humble creatures, and you have set up a barrier against those who would reject his great example...’

Let us also bear in mind that within the Sufi tradition, to which both the Emir and Imam Shamil belonged, spiritual realization cannot but result in compassionate radiance. Realization of the Absolute is, inescapably, radiation of mercy, since as we noted above, mercy and compassion are of the essence of the Real. If compassion in the fullest sense thus flows from realization, this realization itself is the fruit of victory in the greater jihad, to which we now turn.

“As for those who exert themselves in Us, We surely guide them unto our pathways” (Qur’an 29:69)

The principle expressed in this verse is indispensable for a correct understanding of the nature of jihad (holy exertion) in Islam; and it helps to establish a clear criterion by which the deviation of jihadist ideology can be gauged. The exertion or effort in question has to be in God, and not just for God; in other words, it must be conducted within a divine framework and thus be in harmony with all the spiritual and ethical qualities that pertain to that framework; only on this condition will God guide the mujahideen along the appropriate paths, whether the exertion in question be conducted in the realm of outward warfare, moral and social endeavor, intellectual and scholarly effort, or, at its most profound, spiritual struggle against that greatest enemy, one’s own congenital egotism. In this conception of jihad, the end does not justify the means; on the contrary, the means must be in total conformity with the end: if one’s struggle is truly for God, it must be conducted in God‚both the means and the end should be defined by divine principles, thus encompassed and inspired by the divine presence. The employment of vile means betrays the fact that the end in view is far from divine; instead of struggling for God and in God, the goal of any jihad in which the murder of innocents is deemed legitimate cannot be divinely inspired; even if decked out in the trappings of Islamic vocabulary, it can only emerge as a product of a thoroughly un-Islamic jihadist ideology.

In this light, it is wholly understandable that, in the aftermath of the brutal attacks of September 11, many in the West and in the Muslim world are appalled by the fact that the mass-murder perpetrated on that day is being hailed by some Muslims as an act of jihad. Only the most deluded souls could regard the attacks as having been launched by “mujahideen,” striking a blow in the name of Islam against “legitimate targets” in the heartland of “the enemy.” Despite its evident falsity, the image of Islam conveyed by this disfiguration of Islamic principles is not easily dislodged from the popular imagination in the West. There is an unhealthy and dangerous convergence of perception between, on the one hand, those—albeit a tiny minority—in the Muslim world who see the attacks as part of a necessary anti-western jihad, and, on the other, those in the West—unfortunately, not such a tiny minority—who likewise see the attacks as the logical expression of an inherently militant religious tradition, one that is irrevocably opposed to the West.

Although of the utmost importance in principle, it appears to matter little in practice that Muslim scholars have pointed out that the terror attacks are totally devoid of any legitimacy in terms of Islamic law (sharia) and morality. The relevant legal principles—that jihad can only be proclaimed by the most authoritative scholar of jurisprudence in the land in question; that there were no grounds for waging a jihad in the given situation; that, even within a legitimate jihad, the use of fire as a weapon is prohibited; that the inviolability of non-combatants is always to be strictly observed; that suicide is prohibited in Islam—these principles, and others, have been properly stressed by the appropriate sharia experts; and they have been duly amplified by leaders and statesmen in the Muslim world and the West. Nonetheless, here in the West, the abiding image of “Islamic jihad” seems to be determined not so much by legal niceties as by images and stereotypes, in particular, in the immediate aftermath of the attacks, the potent juxtaposition of two scenes: the apocalyptic carnage at “Ground Zero”—where the Twin Towers used to stand; and mobs of enraged Muslims bellowing anti-Western slogans to the refrain of “Allahu akbar.”

In such a situation, where the traditional spirit of Islam, and of the meaning, role, and significance of jihad within it, is being distorted beyond recognition, it behooves all those who stand opposed both to media stereotypes of jihadism and to those misguided fanatics who provide the material for the stereotypes, to denounce in the strongest possible terms all forms of terrorism that masquerade as jihad. Many, though, will understandably be asking the question: if this is not jihad, then what is true jihad? They should be given an answer.

Islamic Principles and Muslim Practice

While it would be a relatively easy to cite traditional Islamic principles which reveal the totally un-Islamic nature of this ideology of jihadis, we believe that this form of argument critique will be much more effective if it is complemented with actions, deeds, personalities, and episodes that exemplify the principles in question, thereby putting flesh and blood on the bare bones of theory. For it is one thing to quote Qur’anic verses‚quite another to see them embodied in action... (ref to Saladin). There is a rich tradition of chivalry from which to draw.

Mercy and Compassion Express the Fundamental Nature of God

Mercy, compassion, and forbearance are certainly key aspects of the authentic spirit of jihad; it is not simply a question of fierceness in war, it is much more about knowing when fighting is unavoidable, how the fight is to be conducted, and to exercise, whenever possible, the virtues of mercy and gentleness. The following verses are relevant in this regard:

“Warfare is ordained for you, though it is hateful unto you. Mohammed is the messenger of God; and those with him are fierce against the disbelievers, and merciful amongst themselves. And fight in the way of God those who fight you, but do not commit aggression. God loveth not the aggressors...”

Repeatedly in the Qur’an, one is brought back to the imperative of showing mercy and compassion wherever possible. This is a principle that relates not so much to legalism or sentimentality as to the deepest nature of things; for, in the Islamic perspective, compassion is the very essence of the Real. The divine creative force is, again and again in the Qur’an,identified with ar-Rahman; and the principle of revelation itself, likewise, is identified with this same divine quality... This ontological imperative of mercy must always be borne in mind when considering issues connected with warfare and Islam. The examples of merciful magnanimity which we observe throughout the tradition of Muslim chivalry are not simply instances of individual virtue, but above all, natural fruits of this ontological imperative; and no one manifested this imperative so fully as the Prophet himself. Indeed, Saladin’s magnanimity at Jerusalem can be seen as an echo of the Prophet’s conduct at his conquest of Mecca...

Contrary to the prevalent misconception that Islam was spread by the sword, the military campaigns and conquests of the Muslim armies were, on the whole, carried out in such an exemplary manner that the conquered peoples became attracted by the religion which so impressively disciplined its armies, and whose adherents so scrupulously respected the principle of freedom of worship. Paradoxically, the very freedom and respect given by the Muslim conquerors to believers of different faith-communities intensified the process of conversion to Islam. Arnold’s classic work, The Preaching of Islam, remains one of the best refutations of the idea that Islam was spread by forcible conversion. His account of the spread of Islam in all the major regions of what is now the Muslim world demonstrates that the growth and spread of the religion was of an essentially peaceful nature. The two most important factors in accounting for conversion to Islam were Sufism and trade. The mystic and the merchant, in other words, were the most successful missionaries of Islam...

The Greater Jihad

While the Emir fought French colonialism militarily, in the following century, another great Sufi master in Algeria, Shaykh Ahmad al-Alawi, chose to resist with a peaceful strategy, but one which pertained no less to jihad, in the principial sense of the term. One has to remember that the literal meaning of the word “jihad” is effort or struggle, and that the greater jihad was defined by the Prophet as the jihad an-nafs (the war against the soul). The priority thus accorded to inward, spiritual effort over all outward endeavors must never be lost sight of in any discussion of jihad. Physical fighting is “the lesser jihad” and only has meaning in the context of that unremitting combat against inner vices, the devil within, that has been called the greater jihad...

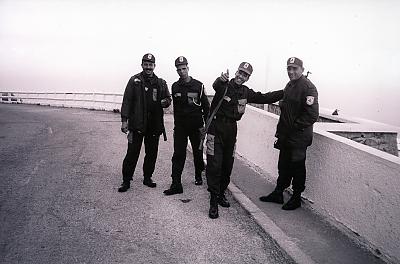

Local police guarding the cathedral of Santa Cruz in Oran

The individual’s moral and spiritual effort in this inner struggle is a necessary but not sufficient condition for victory; only by means of heaven-sent weapons can the war be won: sacred rites, meditations, incantations, invocations, all of which are summed up in the term “remembrance of God.” In this light, the strategy of the Shaykh al-Alawi can be better appreciated. It was to put first things first, concentrating on the ‚“one thing needful‚” and leaving the rest in God’s hands. It might be seen, extrinsically, as an application, on the plane of society, of the following esoteric principle, enunciated by one of his spiritual forbears, Mulay Ali al-Jamal: “The true way to hurt the enemy is to be occupied with the love of the Friend; on the other hand, if you engage in war with the enemy, he will have obtained what he wanted from you, and at the same time you will have lost the opportunity of loving the Friend.”

The Shaykh al-Alawi concentrated on this love of the Friend, and of all those values connected to this imperative of remembrance, doing so to the exclusion of other, more overt forms of resistance, military and political, against the French. The Shaykh’s spiritual radiance extended not just to a few disciples but, through his many muqaddams (spiritual representatives), to hundreds of thousands of Muslims whose piety was deepened in ways that are immeasurable. The Shaykh was not directly concerned with political means of liberating his land from the yoke of French rule, for this was but a secondary aspect of the situation: the underlying aim of the French ‚“mission civilisatrice‚” in Algeria was to forge the Algerian personality in the image of French culture; so, in the measure that one perceives that the real danger of colonialism was cultural and psychological rather than just territorial and political, the spiritual indomitability of the Shaykh and his many followers assumes the dimensions of a signal victory. The French could make no inroads into a mentality that remained inextricably rooted in the spiritual tradition of Islam...

Lest this approach be regarded as a prescription for unconditional quietism, one should note that the great warrior, the Emir himself, would have had no difficulty whatsoever in asserting its validity: for even while outwardly engaging with the enemy on the battlefield, he was never for a moment distracted from his remembrance of “the Friend” It was without bitterness and rage that he fought; and this explains the absence of any resentment towards the French when he was defeated by them, submitting to the manifest will of God with the same contemplative resignation with which he went into battle with them in the first place.

Author in the cathedral with new friend

The episodes recounted here as illustrations of authentic jihad should be seen not as representing some unattainably sublime ideal but as expressive of the sacred norm in the Islamic tradition of warfare; this norm may not always have been applied in practice‚ one can always find deviations and transgressions‚ but it was continuously upheld in principle, and, more often than not, gave rise to the kind of chivalry, heroism, and nobility of which we have offered a few of the more striking and famous examples here. The sacred norm of chivalric warfare in Islam stood out clearly for all to see, buttressed by the values and institutions of traditional Muslim society. It can still be discerned today, for those who look hard enough, through the hazy clouds of passion and ideology.

It is far from coincidental that both the Emir and Imam Shamil, to mention other noble warriors who resisted the imperialist aggression of the West, such as Umar Mukhtar in Libya, the Mahdi in Sudan, and others were affiliated to Sufism. No one need claim that Sufism encompasses Islamic spirituality in an exclusive manner; but no one can deny that the spiritual values of Islam have been traditionally cultivated and brought to fruition most effectively and most beautifully by the Sufis. And it is these spiritual values that infuse ethical norms in whatever domain with vivifying grace, the grace without which the acts of heroism and nobility surveyed here are scarcely conceivable. Sufism did not invent the spiritual values of Islam; it merely sought to give life to them, from generation to generation... (see these recommended links: http://www.ibnarabisociety.org/ and http://www.uga.edu/islam/Sufism.html)

Today, Sufism is a name without a reality; formerly it was a reality without a name. In other words, the values proper to Sufism are deemed to have been present at the time of the Prophet and his companions, where their reality was lived rather than named. After giving us this definition, al-Hujwiri adds that those who deny Sufism are in fact denying the whole sacred law of the Apostle and his praised qualities. It might seem surprising to assert that a denial of Sufism is tantamount to a denial of the whole sacred law, but the stress here should be on the word “whole.” For, if Islam is reduced to merely a mechanical observation of outward rules, then it is not a religion in the full sense; or, it is a religion without inner life: hence we find the great al-Ghazali naming his magnum opus Revival of the Sciences of Religion; and, it is clear from his writings that the spiritual values proper to Sufism provide this inner life of religion.

Author in the cathedral with new friend

It is the Sufis, traditionally, who have most deeply assimilated the universality proper to the Qur’anic message. It is no surprise, then, that those most steeped in Sufism were the ones most sensitive to the sanctity of human life, to the innate holiness of the human being, whatever his or her religion; nor is it a surprise that those most hostile to Sufism are those who demonstrate the most appalling disregard for the inviolability of human life. It is becoming increasingly obvious to intelligent observers of the Muslim world that those most inclined to violence are members of deviant takfiri offshoots of various radical movements that are not only purely ideological‚ but also most hostile to Sufism and to many of the values held most sacred within the spiritual tradition of Islam. Now, such vehement opposition to the spiritual values of the tradition cannot but entail a desacralization of religion at its core; and this, inevitably, goes hand in hand with a rejection of the sacredness of other traditions. The political vilification of the religious “other” is all the more easily accomplished in a climate where the integrity of the sacred within ones own tradition has already been undermined. From attacking the sacred within oneself, it is but a short step to destroying the religious other. One who has become insensitive to the sacred within one’s own tradition is unlikely, to put it mildly, to be respectful of the religious other.

Sufis, such as those we have presented here, on the contrary, are keenly aware not just of the intrinsic holiness of the religious other but also of the sacred manifestations within the religion of the other. The Emir, upon being confronted by the Church of Madeleine, uttered these words: ‚“When I first began my struggle with the French I thought they were a people without religion... Such churches as these would soon convince me of my error..”

What we are witnessing today is the result of a long process of desacralization that has been working itself out within the body politic of the Muslim world: selfrighteousness masquerading as virtue, sanctimoniousness replacing sanctity, sacrilege taking the place of religion‚ Such is the spectacle that unfolds as Islam is being reduced from a way of salvation to the pretext for a this-worldly, political ideology with a religious facade. This reductionism is most apparent in that tiny minority of political extremists who claim to represent the Muslim umma (community), but who manifest only the most violent consequences of the spiritual decline within the umma. However, it should be stressed that the reason why the extremists act in the name of the religion is that the majority of Muslims are still “religious” to whatever degree. In other words, the extremists recourse to religious vocabulary in the effort to legitimize jihadist ideology is itself a testimony to the continuing salience of religion in the Muslim world.

War within the Muslim World: The Real War Against Terrorism

The body politic of the Muslim world has indeed been infected by a poison which is now running riot within it; but it is also receiving, from without, violent assaults which are further weakening the body in its effort to eliminate the poison. What Muslims need to do is to diagnose the poison and show that the tendency to resort to terrorism is a poison afflicting Islam; it is not a product of the essence of Islam. To make such a diagnosis is part of the battle against terrorism‚ indeed, the real ‚“war on terror‚” is being fought on this field, between Muslims themselves. The greatest warriors in this battle are those who fight intellectually to reclaim Islam, to revive its deepest and most noble ideals, in whose light the extent of the deviation currently being paraded as “Islamic” can be clearly seen...

One of the truly great mujahideen in the war against the Soviet invaders in Afghanistan, Ahmed Shah Massoud, fell victim to a treacherous attack by two fellow Muslims, in what was evidently the first stage of the operation that destroyed the World Trade Center. It was a strategic imperative for the planners of the operation to rid the land of its most charismatic leader: a hero who could credibly be used by the West as a figurehead for the revenge attack on Afghanistan that was provoked, anticipated, and hoped for, by the terrorists. But, politics aside, the reason why Massoud was so popular was precisely his fidelity to the values of noble warfare in Islam; and it was this very fidelity to that tradition that made him a dangerous enemy of the terrorists‚ more dangerous, it may be said, than that more abstract enemy, the West. To present the indiscriminate murder of western civilians as jihad, the values of true jihad needed to be dead and buried.

The murder of Massoud was thus doubly symbolic: he embodied the traditional spirit of jihad that needed to be destroyed by those who wished to assume its ruptured mantle; and it was only through suicide—subverting one’s own soul—that this destruction, or rather, this apparent destruction, could be perpetrated. The destruction is only apparent in that, on the one hand, They destroy [but] themselves, they who would ready a pit of fire fiercely burning [for all who have attained to faith]. And on the other hand: Say not of those who are slain in the path of God: They are dead. Nay, they are alive, though ye perceive not.

New friends saying goodbye

Let it also be noted that, while it is indeed true that the martyr (ash-shahid) is promised Paradise, the true shahid is one whose death bears witness (shahada) to the truth of God. It is consciousness of the truth that must animate the spirit of one who‚“fights in the Path of God”.Fighting for any cause other than the truth cannot be called a ‚“jihad,” just as one who dies fighting in such a cause cannot be called a “martyr.” Only he is a martyr who can say with utter sincerity, Truly my prayer and my sacrifice, my living and my dying are for God, Lord of all creation...”(6:162)